Burgerim

Over the last 2 years, a company called Burgerim, run by an Israeli named Oren Loni, went from an unknown burger brand to a network of two hundred stores, and more than 1,200 franchise licenses issued across the US. It made over $45 million between 2017 and 2019. Yet, late last year, they company was nearly penniless and on the verge of bankruptcy. Hundreds of its franchisees were broke, some were homeless, and many were stuck in limbo - unable to pay the costs to open their stores, unable to buy food, unable to contact Burgerim corporate to find out what the hell was going on.

How did all of this happen? Loni was able to exploit a lax regulatory system, and use aggressive sales tactics to lure inexperienced people into the restaurant business. His “demo” stores were modern, stylish, and produced good burgers. There were many problems with, well, basically everything else at Burgerim, as this series in Restaurant Business Online explains:

“I’ve never seen anything like this since I’ve been involved in franchising,” said Keith Miller, a franchisee advocate who first started examining problems with the brand last year. “I’ve seen systems collapse. I’ve never seen a system that seemingly isn’t set up as an ongoing business model be created and grow this big.”

This is an understatement! Oren Loni emerged from obscurity in Israel, opening multiple restaurant franchise brands in his home country. The resume he presented to prospective clients in the US was that he’d run successful chains, and was expanding to the US, but:

A 2017 story in the Israeli publication Haaretz paints a different picture. According to the story, the Bandora franchise shut down in late 2015 after signing up dozens of inexperienced franchisees, including many who were apparently owed refunds that were never paid. The story says Loni “fled” Israel just before courts handed down an order forbidding him from leaving.

Loni had started Burgerim - Hebrew for “many burgers”, natch - back in Israel and, after a failed launch in the US due to running afoul of the tax authorities in California, he figured out the recipe in 2017, and started aggressive ad campaigns on social media to lure in prospective franchisees. It worked, and by 2018 he was getting hundreds of prospects a day, his sales team using aggressive tactics to push people to hand over money for licenses almost immediately.

The chain promised a minimal start-up fee and - more importantly - didn’t care whether people had any assets beyond the $50,000 needed to get a license. This led to problems when Burgerim franchisees had to, well, pay for anything else to run their business. The company helped them get loans - more on that later - and even offered to cover some of their rent and leasing fees, but in most cases that was not enough, and the franchises failed, if they even made it to launch. Remember - Burgerim had issued 1,200 licenses, but by 2019 only had around 200 open locations. That’s a thousand people who’d forked over millions and never opened the doors.

There were clearly quite a few problems with the Burgerim business model, but the most glaring was that the company never collected royalties. Royalties, as far as franchises are concerned, are the percentage of sales the franchisor takes to fund their side of the business. Burgerim was entitled to 5% royalties and just…didn’t take them. Basically:

What Burgerim did is akin to Comcast taking the installation fee for a customer’s new cable account and then waiving the monthly subscription charge.

This was one reason the company ended up nearly broke, despite taking in tens of millions. It was also a sign that Loni never really intended to run the franchise as an actual franchise, and was more interested in collecting the license fees and eventually skipping town. Which is what he did:

By December, Burgerim had stopped answering its phones. A message at the company’s headquarters saying it was closed for Thanksgiving remained in place for three weeks, when it was replaced by a generic message and voicemail boxes that were full.

As for Oren Loni, he was gone. Much like he had after Bandora shut down, Loni left the country.

This story seems crazy - like many scams I write about, it seems extremely obvious in hindsight - but the bigger question is how was this allowed to happen? Don’t we have laws that govern franchises, and who can get licenses to run them? Sure we do. It will shock you to learn that they are…not very good laws.

At the federal level, the FTC regulates franchise businesses. They are required to have disclosure documents, which they give to prospects. Burgerim had one of these, because writing a contract is not difficult if you can afford to pay a lawyer. Only nineteen states have some form of franchise regulation, and only a few of those states have legal penalties for franchise fraud. There are no penalties at the federal level. I’ll let this guy put it succinctly:

“There are virtually no protections from scam artists in franchising,” [Robert] Purvin said.

Cool! One fun fact about franchises is that they are not required to disclose revenue or profit projections to prospects. Many new franchises do not do this. However, because there are no real penalties, Burgerim sales reps regularly made assurances to its franchisees that they’d make lots of money. They sometimes made absolutely wild claims, in fact:

One operator was told most franchisees pay off their loans within a year. Another was told the company’s restaurants generate a 23% profit margin, and that the lowest-revenue store generated $800,000 in sales per year.

As the pandemic is showing us, even the best restaurants operate on razor thin margins. 23% is so far out of the realm of possibility for a new burger franchise it is laughable:

“If this was a stock, everyone would be in jail,” said Keith Miller, a franchisee advocate who has investigated Burgerim extensively.

I take issue with comparing Burgerim to a publicly traded company, because it’s far more like one the various Ponzi schemes I write about than it is a Boeing or Amazon. Unfortunately, because our consumer laws suck in the US, schemes like Burgerim are able to flourish, with practically no oversight.

Speaking of oversight, another reason Burgerim was able to keep the charade going for two years was the Small Business Administration, or SBA. The SBA backed many of the loans to Burgerim franchisees, which lent an air of credibility to the operation. If they government says this is legit, it must be! Well:

But an SBA-backed loan is not a guarantee of safety. In fact, about 1 in 5 SBA-backed loans to franchisees fail, according to a 2015 study.

In this case, the SBA did little to determine whether Burgerim was a workable concept, then backed loans to inexperienced operators who risked their homes to take a chance on the brand.

The problem, of course, is that the 20% of people who take out an SBA loan for a franchise that fails are still on the hook for that money, unless they declare bankruptcy. Because Burgerim preyed upon inexperienced people with little to no food industry experience, many of them dumped all of the money they had into a dream. They were assured it was legitimate because they could get government-backed loans to open, and are now penniless. The founder of the chain has fled, presumably to find another country with lax franchise laws and desperate people looking for a way to survive an economic depression.

Instacart

Last week I wrote about DoorDash and the other gig food delivery companies currently lighting vast piles of cash on fire as they attempt to create efficiencies in an already efficient market. So this week, let’s talk about a gig service that is actually thriving during the pandemic - Instacart. The Verge has a piece on how bad the conditions have become at Instacart in the last few months:

In a third case, a 50-year-old shopper named Alejo tested positive and was admitted to the ICU, but he had his claim denied while he was hospitalized. A gig workers group seized on the case to publicly pressure Instacart with a blistering Medium post, and the pressure worked: Instacart paid up, although the company noted that the circumstances were exceptional. But Alejo hasn’t improved. He’s been in the hospital for more than a month now and is still on a ventilator, with his doctors increasingly concerned about organ failure. In the meantime, his stepson Alejandro has gone back to making Instacart runs. With Alejo laid up, it’s the only way to keep the family afloat.

The human stories in the piece are truly horrifying - workers clearly sick with COVID-19, unable to get any form of help or compensation from Instacart, who finds every possible reason to deny their paltry claims. Meanwhile, the company has hit profitability for the first time, on the literal backs of workers like Alejo:

Instacart hit profitability for the first time last month, and it plans to bring in 300,000 new full-service shoppers. It’s on track to process more than $35 billion in groceries this year, which would put it on par with the fifth-largest grocery chain in the country.

In many cases, this is because Instacart has become the de-facto fulfillment platform for many large grocery chains - searching my local grocery stores in Philadelphia I can see they are nearly all using Instacart, some of them exclusively. The platform has grown huge in the past few years, and wields enormous power in the marketplace as Americans under lockdown try to stay safe and fed. So, why does Instacart suck so much?

The same problems that plague DoorDash and all the other gig apps have made Instacart a cutthroat, cruel world for the workers who depend on it for income:

Toward the end of 2019, the company reworked its system for tipping after it was revealed it was quietly taking a share of tips — something many workers describe as simple wage theft.

Stealing tips is par for the course with these awful companies, but Instacart has somehow managed to take it to another level, allowing customers to change or remove tips days after the fact:

Buyers promise a tip when they list a batch, but they can change it for days after the run is completed. It’s led to a practice shoppers call “tip-baiting,” where buyers list a big tip to make sure their batch gets taken, then pull it back after the fact. Instacart defends the system, saying it gives buyers discretion over how much they’re tipping.

In addition to this particularly evil feature, Instacart puts its shoppers on the hook for things entirely out of their control - long lines at stores, damaged goods, or items that are out of stock:

Shoppers would accept a batch of 30 items, wait an hour in line, and find only 12 of them were actually in stock. They could offer substitutions, but buyers didn’t want to hear that there wasn’t any toilet paper on the shelves. Most people ordering from Instacart had no idea how chaotic supermarkets had become. They didn’t have to — that’s why they were ordering online.

“It really pissed off customers,” Cerena tells me. “They didn’t understand that it was completely out of our control.”

[…]

Instacart would recoup the cost of a particular grocery order if buyers refused to pay, but there were lots of other ways angry customers could make life hard for shoppers, like clawing back tips or leaving a zero-star rating. And most of the time, customers didn’t get mad at stores; they got mad at shoppers. Instacart had arbitraged customer anger onto the most vulnerable people in the system.

Instacart set their shoppers up to fail, adding the additional punishment of low star ratings and clawed back tips as customers became increasingly frustrated that they couldn’t get items from stores. Great system!

To further illustrate how disposable the company believes its shoppers are, in February they retooled their commission system to entice new workers and make it difficult to determine how much they’d earn in a given day:

Most controversial was the On Demand model, a shift made in February that tilted the system heavily in favor of newer shoppers and provoked a quiet revolt from veterans of the platform.

[…]

Before this year, shoppers would sign up for hours in advance and be fed batches one at a time, which let Instacart do some algorithmic management of which shoppers got the more complicated or profitable jobs.

By dumping all the orders into one large bucket and letting shoppers fight it out, Instacart was no longer rewarding veterans or trying to feed large dollar orders to people who hadn’t had one in awhile - it was Lord of the Flies now. And, of course, the shoppers who took the “dud” orders that were small or paid very little, were now losing money delivering for the company, while Instacart was doing just fine. Ah, the gig economy.

There is some good news - Instacart workers have staged two walkouts so far, and gig delivery workers are forming their own collectives to agitate for better working conditions, help each other through the crisis, and highlight attempted abuses by gig companies.

Unlike food delivery, grocery delivery is a service that people want to pay for, with Walmart emerging as a big player in the field. However, the differences between a Walmart or Safeway employee packing groceries for a customer to pick up, and Instacart throwing a bunch of random orders into an app and letting “contractors” fight over the scraps, is quite obvious. I am in favor of making grocery shopping as easy as possible - but there is a way to do it that doesn’t blend human exploitation into the business model. Walmart is an example of this - they’ve even grudgingly raised wages during the pandemic - so why do we need Instacart?

Tenant Screening

If you have applied to rent an apartment any time in the last decade, your landlord may have run you through a background screening service. There are lots of them on the market - some are big names you’d recognize, such as TransUnion - and while some of them might be okay, many are very much not okay:

The automated background check for [Samantha] Johnson cast a wide net, looking for negative information from criminal databases even in states where she had never lived and pulling in records for women whose middle names, races, and dates of birth didn’t match her own. It combined criminal records from five other women: four Samantha Johnsons, and a woman who had used the name as an alias—even though the screening report said she was an “active inmate” in a Kentucky jail at the time.

Yeah, not good. This is another case of rogue algorithms being used to deny people access to basic services - in this case, housing. When background checks are outsourced to unaccountable private companies who won’t disclose how their software works, you get things like this:

The screening process happens so quickly and the competition for apartments can be so fierce that prospective renters don’t always know why they were turned down, much less whether an incorrect background report was the cause.

Some screening companies don’t even provide the underlying records to landlords, instead producing a color-coded “risk” score or a thumbs-up or thumbs-down lease recommendation.

Screening company employees have stated in lawsuits that they err on the side of including any possible match, rather than excluding possible errors.

People being turned down for apartments because a company they’ve never heard of may or may not have matched their name to a criminal? In many cases not even providing any details about the reason for the low score? Fantastic.

The background check industry, predictably, does not give a fuck:

Large background firms, including RealPage, CoreLogic, TransUnion, and RentGrow, declined interview requests for this article. They referred specific questions to a trade group, the Consumer Data Industry Association.

Noting the millions of tenant background reports produced each year, the group denied that any systemic problems existed and accused consumer lawyers of being myopic.

“If I sat in a cardiologist’s office all day, all I would see is people with heart problems,” said Eric Ellman, the association’s senior vice president for public policy and legal affairs. He acknowledged that it hadn’t developed any standards for screening accuracy but said the companies had their own policies.

That…is…pretty glib, coming from a guy who chose this as his professional headshot:

…and who was paid $309,821 in 2018, according to ProPublica, to defend companies who unfairly discriminate against renters. He also sued the state of New Jersey for trying to require credit bureaus to publish reports in other languages. So, you know, a real consumer ally.

Anyhow, companies like the ones represented by the Bowtie Asshole are not providing some bespoke service that requires complicated software or lots of overhead, they’re simply cashing in on a trove of public data:

Tenant screening was once confined to a simple credit check with the three major credit bureaus and a few phone calls to references, but it was revolutionized by the advent of cheap or even free, easily available electronic court records. These include criminal records from across the country, sex-offender registries, terrorism watch lists, and housing court records.

Easy access to the troves of data has also made it possible for anyone with a computer to become a background screener: About 2,000 companies offer the service, but that’s only an estimate. Tenant screeners don’t have to register with any government agency.

Yes, why would we want to regulate who has the power to deny someone a place to live? Preposterous!

It turns out tenant screening was left out of strengthened privacy rules and government standards - companies who provide credit reports and employment screening must obey accuracy rules and provide transparency into their reporting methods.

To further compound the problem, because there is no centralized reporting system, it is impossible to find out whether any of the over 2,000 companies providing the services have incorrect information about you. It’s a complete crap shoot.

Meanwhile, screening companies are making absurd profit margins off all the cheap, unreliable data:

In a deposition for another federal lawsuit, a CoreLogic employee said independently verifying reports like these before sending them out “would be an overwhelming task.”

It’s certainly more expensive: Court filings in a federal lawsuit show that RealPage pays one data broker 22 cents for each criminal record by buying data in bulk. The company typically charges landlords $12 per report. If there’s a dispute, the data broker would charge RealPage $7 to hand-check a record, according to the contract, shrinking RealPage’s profits—but not eliminating them.

Many of the victims in the Markup piece have been dealing with these issues for years, having to fight with landlords any time they need to move. The government has fined a few of the companies, but while tenant screening remains an unregulated wild west, they will continue to screw with peoples’ ability to find housing, and give you the middle finger if you have a problem with it.

Faladdin

Do you need a palate cleanser after all that awfulness? I sure do! Luckily, I stumbled across this fantastic piece in Rest of World by Kaya Genç about a fortune telling app that has become wildly popular in Turkey, called Faladdin. It was created by a guy named Sertaç Taşdelen, who has himself become a celebrity in the country. How does it work? It reads your coffee grinds, of course:

It does this by bringing the Turkish tradition of coffee fortune-telling into the Internet age. For centuries, Turks have boiled coffee grinds and water in the same pot, which leaves a residue that practitioners can read like a Rorschach inkblot.

[…]

Every day, more than one million Faladdin users upload photos of their coffee cup grinds, and Taşdelen’s team provides personalized “readings” of them within 15 minutes.

I think this is…great? The app uses a “freemium” model, so Faladdin mostly makes money from ads, and does not extract money from its customers like a standard fortune teller.

Taşdelen learned the art of fal from his mother, who was a well-known author on the subject:

For more than three decades, she ran a pharmacy in the Turkish capital of Ankara, where the future entrepreneur worked after school. As his mother chatted with customers and filled prescriptions, she would make Turkish coffee and tell their fortunes. “They said, ‘It is your fal that cures us, Aunt Binnaz, not the medicine!’” she recollects in her book.

Fortune telling pharmacists! I love it. Genç also explains the history of coffee in the region:

During the Ottoman era, Islamic pilgrims introduced coffee to the region that now includes Turkey. Muslims savored it; according to legend, an ailing Prophet Mohammed was inspired to spread his Islamic empire after the Archangel Gabriel served him Turkish coffee. Istanbul’s Sufi monks sipped coffee to stay awake for nighttime prayers, and the city’s first coffee shop, or kahvehane, opened in 1554.

That is way cooler than standing in line to visit the original Starbucks in Seattle. When his mother retired, Taşdelen created a blog, then a website, then an app so his mother and her fellow fortune tellers could provide digital readings to customers.

Since we’re talking about fantasy realm already, let’s sprinkle in some AI. Concerned about the human bottleneck in delivering what had now become thousands of readings per day, Taşdelen enlisted OpenAI to help:

Faladdin collects data from users and then draws language from a pool of preformulated interpretations. These readings are produced by a group of 30 contributors, including a dramatist, a psychologist, an ad director, and an author. “They are like the precogs in ‘Minority Report,’” Taşdelen said of his writers. “They possess the psychic ability to see the future, but of course we don’t house them in pools.”

I’d like to think that if my day job making ads doesn’t work out, I could read virtual coffee grounds on an app for a living. Though I’d want to do it from a pool.

The author visited an in-person fal shop last year for the story, and I have to include this quote because it is delightful:

“I want Murat,” a Melekler Kahvesi customer said from an adjacent table. Dressed up for the occasion, she was distressed to learn that Murat was on “indefinite leave.” “Murat’s work model consists of piling up money and disappearing,” a waitress explained, which the customer eventually accepted: “So much bad energy is involved in fal,so I suppose Murat is exhausted.”

If you spend as much time reading about con artists as I do, you inevitably run into psychics and fortune tellers. Their usual M.O. is to do exactly what Murat had done to that Turkish cafe. Typically, however, customers of these grifters do not accept the disappearance with the same calm resignation as the cafe-goer in the story. We could learn a lot from the Turks.

I think Faladdin is fantastic, and I hope it continues to prosper in a way that does not involve its customers forking over money. I’d hate to have to write another piece about Taşdelen in my blog, because I find I quite like him. I’ll close with my favorite quote of his:

Taşdelen denies that he’s spying on anybody. “We don’t do that. We just consider the demographics that users give us,” he said. Faladdin wants to know four things about you: age, gender, job, and relationship status. From there, it’s not difficult to extrapolate. “Single people at a certain age consider marriage. Parents ponder prospects for their kids. Humanity’s algorithm,” he mused, “isn’t complex. Societal expectations make our worries quite predictable.”

I spend a lot of my life studying and trying to decode humanity’s algorithm. Maybe I just need some coffee grounds and machine learning?

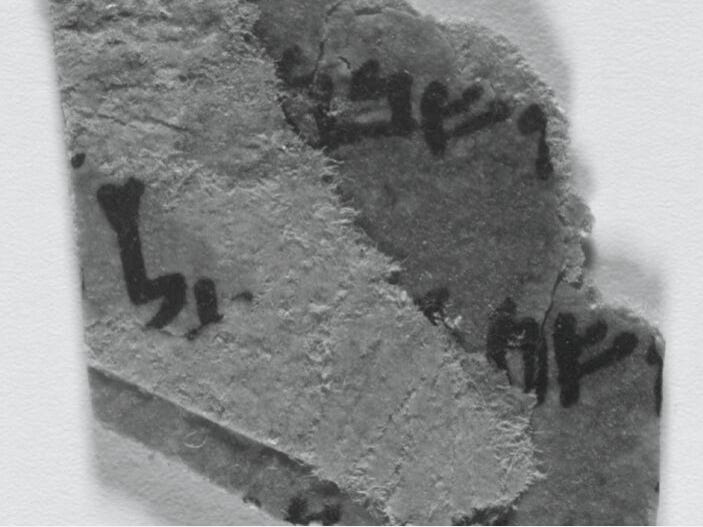

The Real Deal

I have written a few times about the Museum of the Bible and their fake and/or stolen fragments of ancient Biblical texts. Well…good news! This is not another story about that. In fact, it’s the opposite! Scholars in Manchester have discovered that there was hidden text on one of the authentic Dead Sea scrolls they had in their collection. Neat! It wasn’t hidden, so much as difficult to read, because they were afraid of damaging the very fragile artifacts to get at the wording, but hey. I am happy for the guy who made the discovery, who seems ecstatic in the interview. This is what real Biblical scholarship looks like. The Museum of the Bible should take note.

Corona Stuff

The governor of New York quietly gave immunity protections to hospitals and nursing homes during the pandemic, whose lobbying group gave his campaign $1 million dollars. A former White House official got $3 million to provide masks to Navajo hospitals, and some may not work. Wired writes about the Nigerian gangs allegedly involved in the unemployment thefts. Buzzfeed has a guide to the fake experts pushing coronavirus myths and pseudoscience online.

Short Cons

CNBC - “The Department is asking all airlines to revisit their customer service policies and ensure they are as flexible and considerate as possible to the needs of passengers who face financial hardship during this time.”

SEC - “The Securities and Exchange Commission today announced that it has filed an emergency action and obtained a temporary restraining order and asset freeze against a California-registered investment adviser and his entities to halt an ongoing Ponzi scheme targeting senior citizens in Southern California.”

Financial Post - “U.S. tech giant Facebook Inc. will pay $9.5 million but admit no wrongdoing as part of a settlement agreement with the Competition Bureau of Canada over privacy claims the company made in connection to the Cambridge Analytica scandal.”

Tips, comments, and coffee readings to scammerdarkly@gmail.com