Google

Boy! It’s been a busy year for Google. In October, the government accused it of illegally creating and protecting a monopoly over web search. Earlier this week, ten state Attorneys General filed a suit claiming Google built a monopoly in the digital advertising market, colluding to fix prices and pocket big profits. And a day later 30 more states got in on the action, seeking to combine their case with the Justice Department’s and prove that Google’s dominance of the search market came through illegal and unfair means.

So. It’s a lot to take in. Rather than offer a legal analysis - something I am in no way qualified to do - I will try to explain what Google stands accused of doing and how it’s doing it. Where we’re going, we’ll need headers.

Google Ads

First, let’s tackle the advertising market. In addition to its ubiquitous search product, which has become increasingly stuffed full of ads, Google owns a majority share of what is called “display” advertising - banner and text ads that appear on webpages. How this works - again, roughly speaking - is website owners put Google’s code on their pages, and Google pays them a cut of the advertisements it shows to visitors. Advertisers must go through Google to buy these ad placements, and Google sets the pricing.

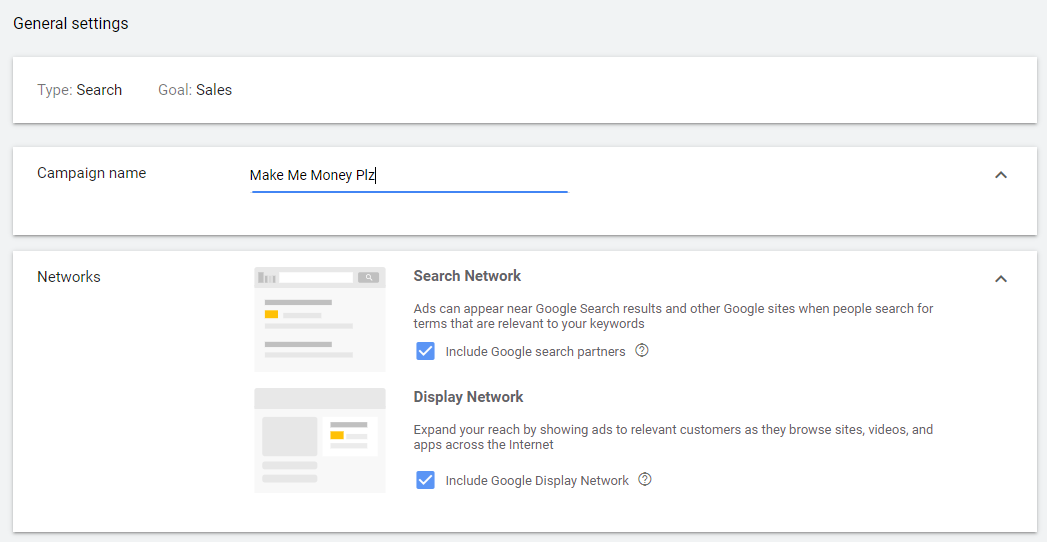

Google makes the process of buying ads on its display platform seamless - even giving search advertisers the option to run display ads by default:

Advertisers may even appreciate this simplicity. Taking a step back, however, there are glaring problems with the arrangement. First - what is stopping Google from overcharging advertisers? The answer is, not much. Advertisers could theoretically cap what they’re willing to pay for advertising “impressions” - each time an ad is shown on a page - but how are they able to accurately measure what an ad is really worth when the prices are set by computer equations they don’t have access to? The DoJ and Attorneys General argue that, in addition to inflating prices and taking an outsized cut of the auction, Google engaged in anticompetitive behavior to force advertisers to use its platform, and pay whatever it asked.

And what of the “publishers” - the operators of the websites who run Google’s code and display ads on its network? If they are large enough they may have the clout to negotiate with the search giant for a bigger share of the ad revenues, but the vast majority are completely at the mercy of Google’s algorithms. It’s a conundrum for them - if they sign with a Google competitor for a bigger revenue share, they lose access to the massive ad marketplace Google controls. And they certainly can’t count on Google working on their behalf to get top dollar for their ads, because Google positions itself as a neutral platform - it couldn’t care less who buys or sells the ads, as long as it gets its cut. In fact, Google reserves the right to claw back funds from publishers if they break the rules, and it pays out ad proceeds months in arrears, despite collecting cash from advertisers in nearly real time.

For an in-depth explanation of how these markets work, and a breakdown of the Texas AG’s surprisingly lucid lawsuit, Shoshana Wodinsky at Gizmodo has more, including how Facebook got in the action:

According to the AG’s investigations, Facebook didn’t move into header bidding to compete with Google, but instead to “draw Google in” and force a deal. And it apparently worked: The following year, the two companies allegedly came to an agreement that Facebook would “curtail” its header bidding biz and instead route that ad business through Google’s ad platform instead. In return, Google promised that the Facebook Audience Network (FAN)—its third-party ad serving product you can read all about here—would get certain advantages that other platforms didn’t, according to the lawsuit.

Of course. Of course Facebook was doing antitrust along with Google. We’ll get to Facebook next week.

Google Search

Okay, on to search. When we think search, we think of the text bar on Google’s website, or a mobile phone. Ask it a question, and complicated algorithms crawl a large database of information to find the most relevant result. Simple, right? Of course it’s not. Those websites don’t show up in Google by magic - the company needs permission to crawl and index them. An owner of a website can insert code in their page to block Google’s web crawlers - but why would they? Empires have been built on “organic” - un-paid - Google search results, and many companies consider search traffic a critical part of their business model. Google is by far the biggest search company, with nearly 90% of the market. So, of course, Google uses its size to unfairly squeeze out competition.

One way it does this - explained in this very good NY Times piece - is through inertia. Google has the biggest website index, and the most extensive search history database, and no competitor can come close:

Websites and search engines are symbiotic. Websites rely on search engines for traffic, while search engines need access to crawl the sites to provide relevant results for users. But each crawler puts a strain on a website’s resources in server and bandwidth costs, and some aggressive crawlers resemble security risks that can take down a site.

Since having their pages crawled costs money, websites have an incentive to let it be done only by search engines that direct enough traffic to them. In the current world of search, that leaves Google and — in some cases — Microsoft’s Bing.

Google and Microsoft have spent years and billions of dollars building web crawlers and comprehensive indexes of the Internet - but Google’s dwarfs even its closest rival. Nearly every site in world is happy to have Google crawl their pages, but any new start-up would have to spend a small fortune to convince companies to allow them to do the same.

Is this Google’s fault, or is it simply a matter of luck, since they were one of the first and emerged as the best search engine a decade ago? Probably a bit of both. But, as in all things it does, Google used its size and bankroll to push other companies out of business. If that failed, it created competing products and displayed them ahead of competitors in its powerful search rankings.

Indexing websites is a challenge for a company seeking to create a search engine, but other search-based directories have thrived - think Yelp, Expedia, or Angie’s List. So what did Google do? Created its own competitors - Google Local, Google Flights, and other directory-style features on Google Maps. It pushed third-party directories down below its own search listings - Google Shopping appears above Amazon listings on a product search, and Google is heavily incentivizing merchants to use their platform.

Customer acquisition is a major barrier to entry for a new directory search or services provider - if you want to create a travel or product review site, you have to spend money to get people to visit it, and build publicity. Google not only has a captive audience of billions, it already knows the most popular products and services people are searching for, so it can develop “native” service offerings like Google Local and shove competitors down in the rankings. While Google does pay a lot of money to run its search platform - compared to any other business, Google’s customer acquisition cost for its new services is nearly zero, because people are already on it, using it to find things. How can companies compete with this? The answer is, they really can’t.

And so, here we are. Google is facing multiple lawsuits and criminal investigations by the US government, not to mention pressure from European regulators. How has it gotten to this point? Google is worth $1.2 trillion dollars and has armies of lawyers and lobbyists who protect it from scrutiny. Also, from the average consumer’s point of view, most of the products Google offers seem good? They’re free! I am a regular user of Google Search and Google Maps, and I’m also an enabler - I upload photos and reviews to Google Local as a “Guide” to help others find good places to eat and drink. The problem is when we only have Google, we have to trust they’re providing us with good services, but we have no way of knowing whether they are. In many cases, as these lawsuits allege and documents reveal, they are concerned only with their financial bottom line. No company should be as big as Google is, or have as much control over what people see, and - perhaps most importantly - what they don’t see.

These cases will likely take years to wind their way through the justice system, and Google has nearly unlimited funds to spend defending itself from litigation, as it now faces an existential threat. I am glad that smart writers and journalists are able to explain a complicated, tricky business in language the average reader can understand, because consumer backlash against Google and its practices may be the most effective tool we have to force the company to behave, until lawmakers or regulators can step in and do it on our behalf.

Asset Forfeiture

In some states, police can seize cash and property belonging to suspected criminals, even if they aren’t ever charged with a crime. Sometimes they keep it, or sell it, or use it to buy military weaponry. Pretty cool, right? Vox explains the tortured legal logic that got us here:

After someone is convicted of a crime, the government's allowed to seize property related to that crime (such as a car that was used to commit a robbery, or money earned selling drugs). That's called criminal forfeiture, and that's not something most people have a problem with.

But there's also a principle in the law, going all the way back to English common law, that says that when property is involved in a crime, the government can start legal proceedings against the property itself for "participating" in criminal activity. The property doesn't get charged with a crime — instead, it's sued by the government, in a civil lawsuit. (Hence the name "civil asset forfeiture.")

Federal and state laws give certain protections to people who are charged with crimes in criminal court. But those protections don't apply to people who are sued, or people whose property is sued. So in civil forfeiture cases, the government usually doesn't have to work as hard to prove that property was involved in a crime as it would in a criminal case. And that's assuming that the case goes to court at all.

Cool. For years justice advocates have argued against the practice, highlighting the many ways it’s been abused by law enforcement. In 2015, New Mexico banned the practice, and now there’s a study out showing it was unequivocally a good decision:

The predicted rise in crime and drop in arrests has not materialized, according to the study, which is based on analyses of FBI data. Arrest and offense rates in New Mexico, the study found, remained essentially flat before and after the 2015 law went into effect. That’s based on an examination of crime overall, as well as a specific set of offenses: drug possession, drug sales, and driving under the influence. Arrest and offense rates were also consistent with trends in two neighboring states, Colorado and Texas.

Cops stealing property from suspected criminals didn’t actually deter crime, go figure. Law enforcement claims asset forfeiture helps them take down drug cartels and Bernie Madoffs but in reality it is used mostly against the poor, because of course it was:

The median forfeiture averaged $1,276 across the 21 states where usable data was obtainable. In most of those states, half of cash seizures fell below $1,000. In Michigan, for example, half of all civil forfeitures of currency were worth less than $423, and in Pennsylvania, that median value was $369.

“That’s not drug dealer money,” said Jenny McDonald, a senior research analyst at the Institute for Justice who authored the study. She said she and her colleagues expected the figures to be low, but “just how low they were shocked even us.”

Some police departments went to unbelievably cruel lengths, including my local PD:

Police sometimes target family homes, too. In 2013, ProPublica reported on how prosecutors in Philadelphia sought to seize the houses of often lower-income residents simply because a child or other relative had sold small amounts of drugs while living there. Some of those families spent years in court fighting to save their homes.

Cops became so brazen that in many cases they abandoned the premise that the seizures were meant to compensate victims and instead used it to enrich themselves :

But in at least six of the 15 states that disclose data on how forfeiture funds are spent — including Florida, Illinois, Oregon and Utah — none of the money obtained by civil asset forfeiture went toward paying back victims of crime for what they lost. The other nine states either use negligible amounts to compensate victims or do not specify whether any money goes to victims.

Instead, law enforcement directed the money mostly toward salaries, equipment and other operational expenses. For some law enforcement agencies, forfeiture funds have accounted for as much as 20% of their budgets, and are sometimes used for seemingly nonessential purchases. A police department in Georgia, for example, once spent $227,000 on an armored personnel carrier, and a sheriff in New Mexico splashed out $4,600 for an awards banquet. In one recent case, a suburban Atlanta sheriff spent $70,000 in forfeiture funds on a muscle car, a Dodge Charger Hellcat, that he uses solely to drive to and from work.

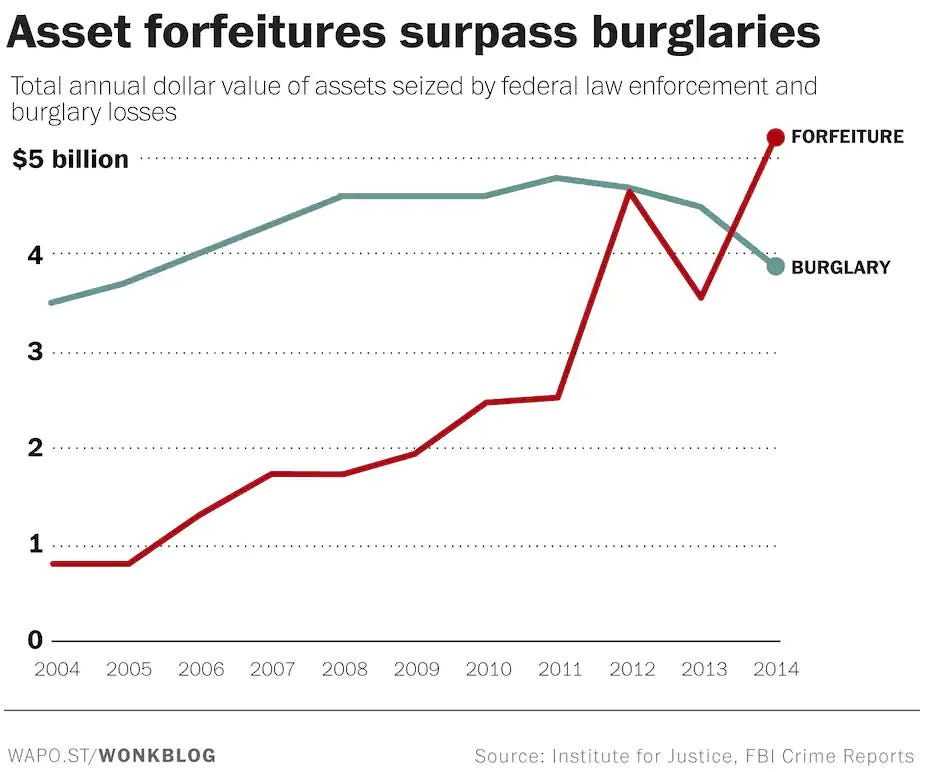

Even Clarence Thomas has expressed doubts that civil forfeiture is Constitutional. As justice advocates push more states to abandon the practice, there is hope we may see its end in our lifetimes. While the Institute for Justice report has some excellent visualizations I’ll link this image from 2015 instead because it’s a perfect distillation of how outrageous the issue has become:

MacKenzie Scott

MacKenzie, the award-winning novelist and ex-wife of Jeff Bezos, has been giving her fortune away at a rapid clip:

MacKenzie Scott is giving away her fortune at an unprecedented pace, donating more than $4 billion in four months after announcing $1.7 billion in gifts in July.

The world’s 18th-richest person outlined the latest contributions in a blog post Tuesday, saying she asked her team to figure out how to give away her fortune faster.

This is good - although it’s a myth charity is better or more efficient than simply paying taxes. It’s not MacKenzie’s fault her ex-husband’s company generated unthinkable wealth and she got half, and the US tax system is so broken she has to shower it on charities since she’s got no other use for it. But, let’s read the next sentence in the article:

Scott’s wealth has climbed $23.6 billion this year to $60.7 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, as Amazon.com Inc., the primary source of her fortune, has surged.

She’s spent $4 billion and made $23 billion by doing nothing! Again, this isn’t a knock on MacKenzie at all, it’s just an illustration of how even the best-intentioned billionaires make so much money they can’t even hire a team of people to give enough of it away to make a dent in their holdings. I’m reminded of this excellent piece in the NY Times about the search for a lost World War II aircraft carrier, when the author describes Paul Allen’s quest to give away his Microsoft fortune:

In 2010, he pledged to give away more than half his wealth. That goal proved impossible within his lifetime: His investment portfolio grew faster than he could spend it. Allen bought superyachts, estates and sports teams that barely dented his pile. He collected vintage planes, guitars and cars. He threw Gatsby-esque parties. He started a minor space program. He also gave $2 billion away in the fields of education, health care, science and the arts, and appeared on The Chronicle of Philanthropy’s list of the 50 most generous Americans 17 years in a row. Nevertheless, he was worth more at the time of his death ($20 billion) than he was in 2010 ($13.5 billion).

I wish MacKenzie luck, but if she’s serious about divesting a fortune her best bet is to subsidize a bunch of progressive political candidates who can pass a wealth tax on people like her husband.

Short Cons

ProPublica - “Rather than openly penalizing Chase, the nation’s largest bank, OCC officials decided to issue a quiet reprimand — a supervisory letter — that would go into the bank’s file and stay out of public view, according to the people and regulatory paperwork.”

UnDark - “Berns […] says that patients often don’t know that their doctors might have a financial stake in the dialysis clinics to which they are referred.”

CRN.com - “SolarWinds majority owners Silver Lake and Thoma Bravo sold $286 million of stock just before the company announced a new CEO and disclosed a cyberattack.”

Tips, thoughts, and tech lawsuits to scammerdarkly@gmail.com