Super League

If you are a fan of soccer, you’ve spent your week following Super League news. If you are not, this NY Times piece explains what happened:

And so, despite all the doubts, the clubs showed their hand just after 11 p.m. on Sunday night in London. An official announcement, published simultaneously on the 12 teams’ websites, revealed that they had all signed up to what they called the Super League. But by then, the narrative that the project was driven by the greed of a few wealthy clubs and their leaders had taken shape.

“It was dead in the water by 11:10,” the executive involved in the plan said. “Everyone had climbed their hill and would not be able to come down.”

Essentially, 12 of the “biggest” European clubs - by revenue, if not on-field achievement - declared they were forming a new international league that they were all guaranteed entry into. There is currently a UEFA Champions League, which features top teams from all the European countries in a knockout tournament. The richest clubs felt they were being shortchanged by the UCL, which distributed money to the dozens of clubs who qualified each year. Also, there was no guarantee of entry - it’s unlikely at least two of the Super League founders from England will make the UCL this year.

So, the owners of the clubs concocted the Super League, behind closed doors, and revealed it earlier this week. They hadn’t counted on the backlash - which makes sense when you consider the plan was cooked up by a bunch of billionaires, many of whom have little interest in the game.

How did things get to this point? The Guardian’s David Goldblatt explains:

First, European football, like everything else, has become much more unequal, with revenue concentrated in a decreasing number of nations, leagues and clubs, while many systems of redistribution have been removed or reduced. One consequence of this inequality is that a handful of top clubs dominate their domestic leagues, and they now feel that only an elite European league will suit them.

[…]

Second, the last decade has seen a sharp increase in the role of investment banks, venture capital and hedge funds in football – as investors and club owners. JP Morgan are the bankers to the ESL; AC Milan are owned by a US hedge fund, while Fenway Sports Group, the owner of Liverpool, is cut from the same cloth.

[…]

Third, there has been a considerable politicisation of club ownership. Berlusconi turned his ownership of AC Milan into a political movement that helped him dominate Italian politics for decades. […] Manchester City and PSG – who have so far declined to join the ESL – are the symbolic linchpins of the foreign policy of the UAE and Qatar. The Gulf states do not need football’s money, but they have other goals that are better served by an absence of public regulation, whether from national football associations or UEFA.

Soccer, European soccer especially, is a wildly popular global sport. These clubs make hundreds of millions’ of dollars in revenue a year, but they’re also expected to spend profligately to recruit the best players, and qualify for the biggest competitions. The Ringer’s Brian Phillips elaborates:

The conundrum, in other words, is that European club soccer is being steered by two contradictory imperatives at the same time. There’s an imperative of attention and money, which tells the big clubs to act as though they’re the center of the universe, and there’s an imperative of sentiment, which tells them to act as responsible members of a community.

[…]

This is not a stable situation! It leads to all sorts of problems: lack of clarity about who’s actually running the game, constant resentment on all sides, massive yet haphazard power shifts (the TV rights deal in Spain, the entire existence of the Premier League) that leave small clubs clinging to life and big clubs annoyed that a translucent sliver of pie still goes to Ipswich Town.

He points out the self-reinforcing problem - fans want to watch the most talented players play one another, and only the big clubs can afford those players, so if those clubs can’t qualify for the international competitions, the fans are being robbed of the chance to see the best talent. The Super League was a ham-handed effort by the rich clubs - by their owners, really, since no one else knew about it - to ensure they got to feature in big games every year, which is what the fans want, but they did it in the most objectionable and tone deaf way imaginable. Predictably, the fans lost their minds.

There’s another, more insidious trend exposed by the Super League’s proposed structure - owners desire to cut player wages. European soccer clubs have two sets of expenses - they have player “transfer” fees which are paid directly to the club they’re buying a player from. Then there’s player salaries, which are negotiated directly with the player and their agent. In some cases, even if a club can afford a player’s transfer fee, they can’t reach an agreement on wages and the deal won’t happen. There are no salary caps in soccer, and the big clubs tend to pay players far more than the smaller clubs. The Super League wanted to change this:

The European Super League statement doesn’t mention a salary cap explicitly, but it does contain a telling reference to a “sustainable financial foundation with all Founding Clubs signing up to a spending framework,” and I would challenge anyone who doesn’t think this means a salary cap to answer: how could such a spending framework leave 70% of club spending untouched?

UEFA considers a 70% wages-to-turnover ratio sustainable - meaning a club is spending 70 cents on talent to make a dollar in revenue. Major League Soccer (MLS) in the US has a 28% ratio. Team owners are looking at their biggest expense - players - and want to cut costs. Soccer fans can expect to see more of this, even though the Super League has failed. Club owners are increasingly rich, and increasingly disconnected from the sport itself. For that matter, so are the people in charge of FIFA, one of the most wildly corrupt sports associations on the planet. There really are no heroes in this story, but at least for now it seems soccer fans have prevailed against the worst of the villains.

Zach Avery

Zach Avery, who the LA Times refers to as a “small-time actor” was arrested and charged with a big-time fraud earlier this month:

Since December 2019, Horwitz’s company has defaulted on more than 160 payments due to his investors, according to the FBI. Its largest investor, JJMT Capital, LLC, of Chicago, is owed more than $160 million in principal and about $59 million in investment profits, Verrastro said.

All told, Horwitz owes investors about $227 million in principal alone, according to the FBI.

Apparently Avery told investors he had strategic partnerships with various media platforms to license foreign distribution rights for films. In 2013, Avery launched 1inMM Capital, claiming he could license film rights at significant profit margins and deliver big returns to investors. He produced forged contracts and agreements with big name studios like HBO and Netflix, and forged additional correspondence when he was unable to make investor payments.

Essentially, Avery ran a Ponzi scheme, which fell apart after a few years as he siphoned off 1nMM’s money to fund his lavish lifestyle. The question is - how did he get more than 160 investors, many of them sophisticated private equity firms, to go along with this for years? Didn’t anyone think to contact HBO or Netflix and ask them about this guy whose acting career, according to the Times, was unremarkable:

As Zach Avery, he appeared in the 2018 sci-fi thriller “Curvature.” A Times review of the film was headlined: “Stylish sci-fi thriller ‘Curvature’ trapped in first dimension.” A Variety critic said the film “wants to get the heart racing and the mind bending simultaneously, but flatlines in both departments.”

Quite the metaphor for his investment business, as it turned out.

Vivian Flores

NBA fans have been…let’s say obsessed with the recent catfish scandal surrounding a popular Lakers fan podcast host:

Toussaint revealed he had never actually met Flores in person. Their first conversation was via Twitter direct message in February 2020 when he checked in on her after the memorial service for Kobe Bryant at Staples Center. They remained in touch, but exclusively online. He said that even as they recorded the podcast together, she refused to video call him, citing her insecurities.

Her co-host hadn’t ever met her or seen her face, which seems a little odd, but okay. The entire mess started because Toussaint had made a post asking for help finding Flores, who then reappeared, claimed she had passed out from her cancer treatments, and posted a video that…didn’t help matters:

A woman also appeared in a video that was posted to the account on Tuesday. Despite the attempts to prove that Flores is a real person, it only fueled the catfishing flames further as the woman held up a sign that said “Vivien” with an “e” instead of an “a.” The account is now inactive.

Apparently the person(s) behind the account had been catfishing people since 2009, which impressive commitment to the craft. I’m unclear why someone would need to catfish their way onto a fan podcast - that was apparently pretty good! - but people are strange. RIP Vivian.

Jobs

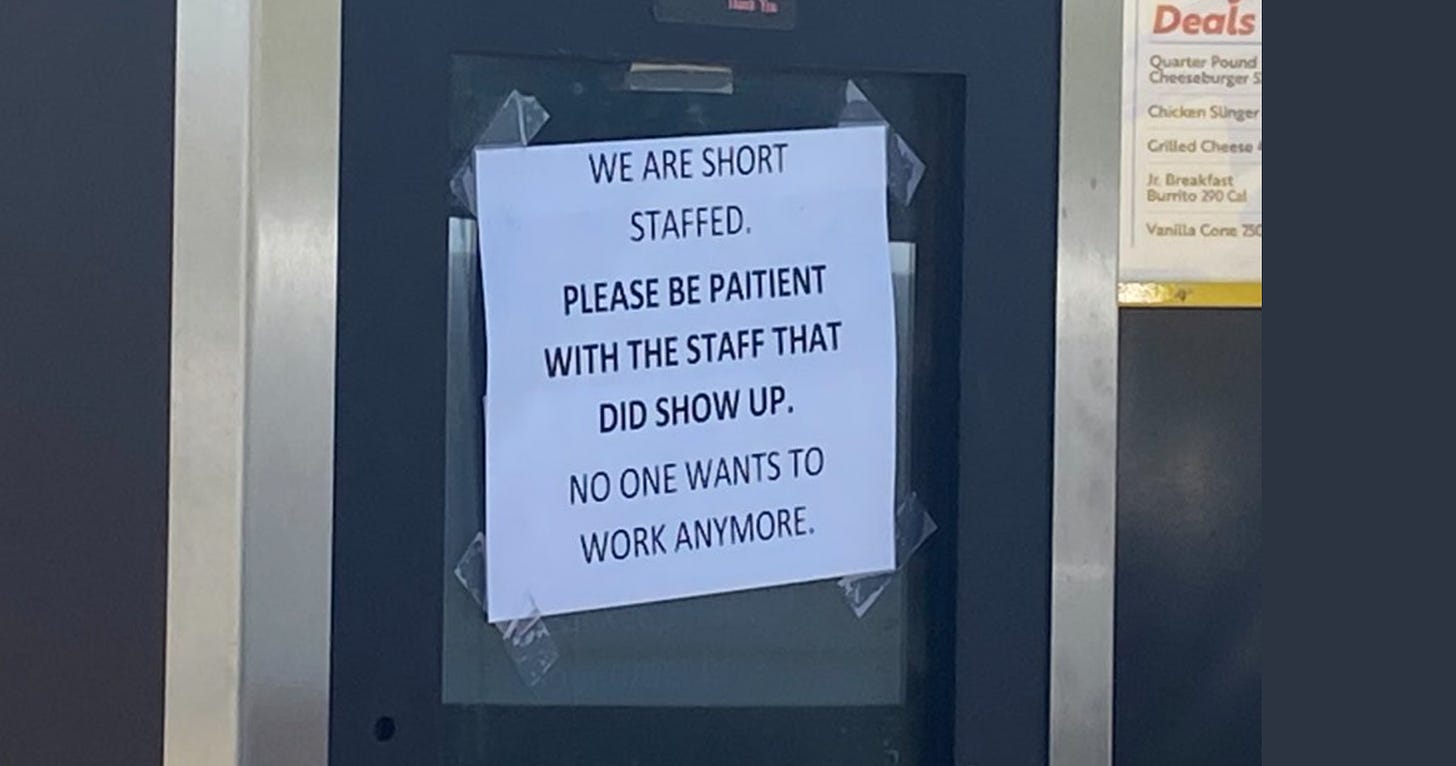

Unemployment in the US is around 6%, which would indicate there are workers available for most open jobs. However:

You will find dozens in which businesses, especially in the restaurant and other service industries, say they face a potentially catastrophic inability to hire. The anecdotes come from the biggest metropolitan areas and from small towns, as well as from tourist destinations of all varieties.

If this apparent labor shortage persists, it will have huge implications for the economy in 2021 and beyond. It could act as a brake on growth and cause unnecessary business failures, long lines at remaining businesses, and rising prices.

Indeed! Anecdotally, restaurants and service businesses seem to be having trouble finding workers:

Business leaders have been quick to blame expanded unemployment insurance and pandemic stimulus payments for the labor shortages.

The logic is simple: Why work when unemployment insurance — including a $300 weekly supplement that was part of the newly enacted pandemic rescue plan — means that some people can make as much or more by not working?

Simple! Or, maybe not. Anne Helen Petersen points out that the real problem may be the exploitative nature of the service economy:

Some of these unfillable jobs are in places without affordable housing — or, like Missoula, where cost of living has continued to rise over the course of the pandemic. Others are seasonal and/or tourist-adjacent. Many are at restaurants, particularly fast-food. Some are at retail stores with unpredictable scheduling. What goes unsaid in many of these stories is the fact that the jobs are shit jobs, whether because of the unsustainability of the pay, the Covid exposure, or the shit treatment they’ll receive from tourists.

Stick with me here, but what if people weren’t lazy — and instead, for the first time in a long time, were able to say no to exploitative working conditions and poverty-level wages? And what if business owners are scandalized, dismayed, frustrated, or bewildered by this scenario because their pre-pandemic business models were predicated on a steady stream of non-unionized labor with no other options? It’s not the labor force that’s breaking. It’s the economic model.

Yup. Elsewhere, Ryan Cooper discusses how bad things have become for gig workers, a situation only made worse by the pandemic:

All these horrible gig companies rely on a large population of people desperate for work. But if jobs are plentiful and labor scarce, then suddenly they will find it a lot harder to fill ruthlessly exploitative positions. They will have to start offering better pay and conditions, forcing them to economize on labor with real innovation or go out of business. Amazon could probably handle it, but many of these other gig companies likely can't.

It turns out gig companies are also having trouble recruiting new workers at the moment. Here in Philly we’ve had multiple “outages” on food delivery apps during peak hours - delivery options simply disappear - presumably because not enough people are willing to drive for substandard wages during a pandemic. Uber and Lyft have gone back to doling out cash:

To sweeten the deal, Uber and Lyft are resorting to generous cash bonuses for driving or referring new drivers, a once-common tactic they’d largely phased out because it led to heavy financial losses. Uber said in April it would earmark an additional $250 million to pay incentives to drivers in the near team.

Considering most gig workers were making poverty wages before the pandemic, it’s not a surprise the industry is finding itself short of exploitable labor.

And, as the newly vaccinated begin to travel again, gig companies are scrambling to prepare:

Airbnb will have to add millions of new hosts to accommodate guests as travel picks up again following the coronavirus pandemic, CEO Brian Chesky told CNBC.

“To meet the demand over the coming years, we’re going to need millions more hosts,” Chesky said in an interview…

Maybe…millions more people don’t want to rent out their homes to strangers on your illegal hotel app? I don’t know. Unfortunately, gig companies are still too rich to fail outright, buoyed by investors and a bullish stock market, but here’s hoping that the same employees we lauded as “essential” a year ago finally realize they deserve much better than they’ve been getting up to this point. They should stop taking shitty restaurant jobs and open their own restaurants. They should stop driving for gig companies and unionize, or go do literally anything else, because only a shortage of labor willing to be exploited by capital will make any real or lasting change.

Short Cons

NY Times - ““She’s just a con artist, it’s really sad to say. And she’s really good at it. She has been her whole life,” Ms. Lindstrom said. “She can talk anybody into anything.””

WaPo - ““I accept full responsibility, I make no excuses, no justification, and I am truly, truly remorseful,” said Boice, 41, who had billed his company Trustify as an “Uber for private investigators.””

VICE - “Facebook wants to "normalize" the idea that large scale scraping of user data from social networks like its own is a common occurrence, as the company continues to face fallout from a leak of over 500 million Facebook users' phone numbers.”

Tips, thoughts, or Manchester club disqualifications to scammerdarkly@gmail.com