Ivermectin

Ivermectin is an anti-parasitic drug, most commonly used in livestock, who deal with a lot of parasites. It’s in the news because lots of people have been taking it to treat or prevent COVID-19, which it does not do. In fact, because most people who are taking the drug are using livestock-sized doses, there is significant risk of serious health problems and overdose.

So, uh, how on earth did we get here? It began with a group called the Front Line Covid Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC):

In the very early days of COVID, months before ivermectin entered the picture, Dr. Paul Marik, Dr. Pierre Kory, Dr. G. Umberto Meduri, Dr. Joseph Varon and Dr. Jose Iglesias — all critical care specialists with various concentrations — came together to swap ideas about how to tackle this unknown virus.

[…]

The original FLCCC goal was to find treatments that worked until vaccines were widely available. In October 2020, the doctors took note of a number of small, successful trials using ivermectin pills to treat and prevent COVID, though the data were considered low-quality in the wider medical community. They jumped at what they saw as an opportunity to stem the pandemic, soon adding ivermectin to the MATH+ protocol, as well as to their new prevention protocol called I-MASK+.

As recently as January 2021 the group was attempting to convince the CDC ivermectin was a COVID-19 cure, but the data they compiled was shoddy:

But after investigating the study’s integrity, Frontiers announced on March 2 that it was rejecting the article because of “a series of strong, unsupported claims based on studies with insufficient statistical significance, and at times, without the use of control groups.” Meanwhile, vaccines were more and more accessible in the U.S. with each passing day, and the FLCCC had still not updated its protocols to include vaccination.

Dr. Kory had become famous among anti-vaxxers after he testified in front of the US Senate that ivermectin was a miracle drug. It fueled claims by Senators and right-wing podcasters and radio hosts that ivermectin was a treatment for or protection against COVID-19.

It’s worth noting that there is a human version of ivermectin, which doctors can prescribe. It’s used to treat parasites in humans, but has not shown any efficacy against viruses. It is not approved by any medical or regulatory body in the US to treat COVID-19, despite a big uptick in the number of prescriptions being written for it - more on that in a minute.

Kory blames the FDA and CDC for the current animal ivermectin craze, saying if they’d simply approved the treatment people wouldn’t be raiding feed stores for it:

“We don’t need their effing approval to prescribe during COVID. It’s called off-label use,” he said. “And now by saying this, you’re injecting the fucking idea of taking animal ivermectin into the population? Now more people are going to run at it. And I’m sorry, but I am not responsible for this fucking insanity. And I can’t correct it.”

He’s far more skeptical about the efficacy of vaccines, and the FLCCC still hasn’t taken a firmly pro-vaccine position, allowing the horse paste conspiracies to spread like wildfire among the anti-vaxx population, and those unvaccinated who may have caught the highly contagious Delta variant.

No story about fringe conspiracy theories and junk science would be complete without a Facebook angle:

The FDA has resorted to begging the public not to use it as a COVID treatment even as public-health officials in Mississippi and Florida report citizens being hospitalized due to overdosing on it; Facebook Groups, both public and private, are nonetheless overrun with bleak, harrowing posts from ivermectin advocates, as well as specific, misguided advice about how to use the drug, and lots of advice on how to obtain it.

Ivermectin true believers are turning to Facebook groups to discuss dosage and other “tips” on how to administer livestock dewormer to themselves and their loved ones. Facebook has a policy against false claims about COVID-19 cures, which it has yet to apply to the ivermectin groups, or to its advertising:

The Ad Library also shows a number of sponsored posts promoting politically-motivated conspiracy theories around ivermectin and COVID, including one from a GOP group in Oklahoma reading, "Why wouldn't we consider and study every possible treatment for an illness? Because it's not about the virus, it's about your freedom."

Facebook claims they are taking down ivermectin ads and groups - months after the movement gained momentum - and even Reddit has started to restrict and take down anti-vaccine groups promoting the drug. That hasn’t stopped sites like SpeakWithAnMD from peddling prescriptions online:

The website advertises consultations for $90 and fills prescriptions through Ravkoo Pharmacy, an online pharmacy that America’s Frontline Doctors advertises as “partners,” who provide “the option to have that prescription delivered right to your door, the same day.” On a SpeakWithAnMD.com intake form viewed by NBC News, prospective patients are asked, “What medication do you prefer?” The user is then presented with three options: “Ivermectin,” “Hydroxychloroquine” or “Not sure.”

The site is affiliated with America’s Frontline Doctors, who are affiliated with the FLCCC, et cetera. As NBC’s investigation shows, ivermectin has been around awhile but has increased in popularity as high profile right wing media personalities have pushed it:

Ivermectin first drew some attention late last year as a possible Covid treatment, with interest remaining reasonably low until July, according to Google search data.

In recent weeks, a variety of conservative figures and anti-vaccination activists have embraced the drug. Fox News hosts Laura Ingraham, Sean Hannity and Tucker Carlson have mentioned it.

Social media sites can belatedly take down groups, or block these conspiracy orgs from running ads, but when prime time Fox News hosts and talk radio personalities are pushing dangerous livestock drugs, it’s unlikely the craze will die down any time soon.

Hospital Pricing

Americans with health insurance may - reasonably - have the expectation that what they pay for a service at a hospital is the best available rate. Their insurance company will have negotiated a good price, and they’ll be responsible for a small amount of it, because that’s how we’re told the system works in this country.

It turns out that’s not what happens at all:

The New York Times partnered with two University of Maryland-Baltimore County researchers, Morgan Henderson and Morgane Mouslim, to turn the files into a database that showed how much basic medical care costs at 60 major hospitals.

The Trump administration created rules requiring hospitals to publish the prices they negotiate with private insurers. The hospital and insurance industries fought it in court and lost. This year, hospitals were supposed to start publishing the data. Many…simply haven’t? But the ones who have paint an ugly picture:

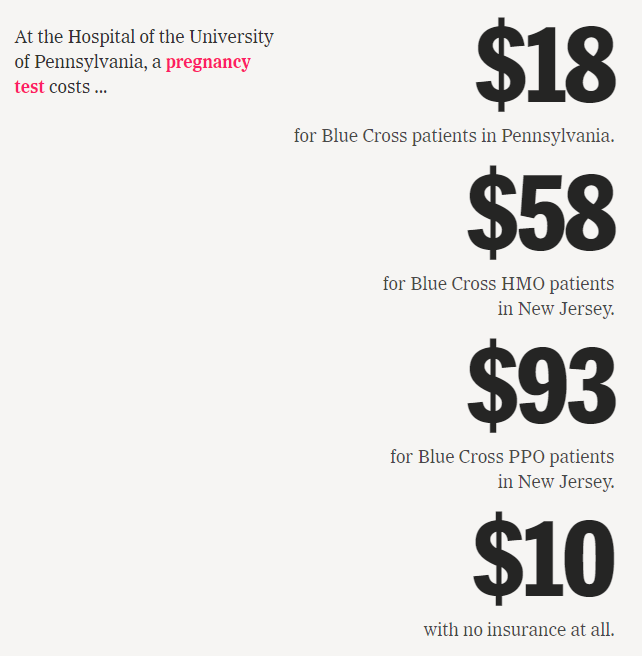

It shows hospitals are charging patients wildly different amounts for the same basic services: procedures as simple as an X-ray or a pregnancy test.

And it provides numerous examples of major health insurers — some of the world’s largest companies, with billions in annual profits — negotiating surprisingly unfavorable rates for their customers. In many cases, insured patients are getting prices that are higher than they would if they pretended to have no coverage at all.

Why would insurers do this? In some cases they’re financially motivated to cut bad deals, because more money spent on care means bigger profits:

Federal regulations limit insurers’ profits to a percentage of the amount they spend on care. And in some plans involving large employers, insurers are not even using their own money. The employers pay the medical bills, and give insurers a cut of the costs in exchange for administering the plan.

This problem extends to employers, who are blocked by insurers from seeing the prices their employees will pay:

Larimer County, in Colorado, covers 3,500 workers and their families in its health plan. In 2018, county officials asked their insurer to share its negotiated rates. It refused.

“We pushed the issue all the way to the C.E.O. level,” said Jennifer Whitener, the county’s human resources director. “They said it was confidential.”

Ms. Whitener, who previously managed employer insurance contracts for a major health insurer, decided to rebid the contract. She put out a request for new proposals that included a question about insurers’ rates at local hospitals.

A half dozen insurers placed bids on the contract. All but one skipped the question entirely.

Can you imagine negotiating a contract to provide health insurance for your employees and the insurance company won’t disclose what their care will cost? Until 2021, this was all perfectly legal, and was in fact industry standard.

So how badly are people being gouged as a result of this? The NYT used Medicare’s reimbursement rates as a guideline, and it wasn’t good:

That gray line is four times what Medicare pays hospitals for a colonoscopy - one of many common preventative procedures that have to be performed at hospitals. The gray dots are smaller insurers, some of whom are more motivated to negotiate better prices, though even those can be confusing:

The data doesn’t yet show any insurer always getting the best or worst prices. Small health plans with seemingly little leverage are sometimes out-negotiating the five insurers that dominate the U.S. market. And a single insurer can have a half-dozen different prices within the same facility, based on which plan was chosen at open enrollment, and whether it was bought as an individual or through work.

It’s staggering to think that the same procedure in the same hospital can be as much as ten times more expensive depending on which insurance plan someone happens to have chosen - or had chosen for them by their employer, which is how the majority of Americans get their coverage.

Hospitals aren’t incentivized to keep costs down either, because nearly every private insurance plan in the US includes deductibles, some of them in the thousands or tens of thousands of dollars, paid out of a patient’s pocket:

Sixteen percent of insured families currently have medical debt, with a median amount of $2,000.

Even when workers reach their deductible, they may have to pay a percentage of the cost. And in the long run, the high prices trickle down in the form of higher premiums, which across the nation are rising every year.

Premium costs are rising each year, costs of service are increasing, and we’ve only just now begun to get a look behind the curtain to see how badly the medical system is gouging patients. I say “begun” because most hospitals are ignoring the new rule:

The potential penalty from the federal government is minimal, with a maximum of $109,500 per year. Big hospitals make tens of thousands of times as much as that; N.Y.U. Langone, a system of five inpatient hospitals that have not complied, reported $5 billion in revenue in 2019, according to its tax forms.

As of July, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services had sent nearly 170 warning letters to noncompliant hospitals but had not yet levied any fines.

Or they’ve tried to make it difficult to parse:

The new price data is often published in hard-to-use formats designed for data scientists and professional researchers. Many are larger than the full text of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Hospitals have long complained that government reimbursement rates make it impossible to provide high quality care, but we’re finally seeing how they make their money, with the help of the multibillion dollar private insurance industry.

The Death of a Hospital

Speaking of hospital reimbursements, let’s dive into the story of Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia. We’ve talked about it before, but the New Yorker has done an in-depth post mortem. For decades, Hahnemann has served Philadelphia’s poor as a for-profit hospital:

Philadelphia is one of the poorest big cities in the United States, with about a quarter of its 1.6 million residents living below the poverty line. Since 1977, when Philadelphia General closed, it has also been the largest American city without a public hospital. Hahnemann, with nearly five hundred beds, occupied a city block on the edge of North Philadelphia, an area that includes several impoverished neighborhoods. A majority of the more than fifty thousand patients that the hospital treated each year had publicly funded medical insurance or none at all; two-thirds were Black or Hispanic.

This means the hospital was primarily relying on Medicare and Medicaid, with lower government reimbursement rates. It was owned by Tenet Healthcare, a Dallas private equity firm that specialized in rehabilitating hospitals with financial difficulties. The way they went about it wasn’t always…legal:

Eight years later, Tenet agreed to pay nearly nine hundred million dollars in fines to the Justice Department for excessive Medicare billing, distributing kickbacks to doctors, and exaggerating the severity of diagnoses in order to inflate charges.

For years Tenet stripped Hahnemann to the bone, failing to replace old equipment or repair the aging building. Tenet also had an advantage over smaller hospital chain owners - its massive size allowed it to negotiate better reimbursement rates and supply costs. When the hospital was sold in 2018 to Paladin Healthcare Capital, things started to change, initially for the better:

In early 2018, Hahnemann received a deep cleaning, which included scrubbing the grout with toothbrushes. For the previous two decades, the hospital had been owned by Tenet Healthcare, a multinational company that had neglected to maintain the facility.

Setting aside the fact the multibillion dollar for-profit entity controlling a key hospital in a major US city hadn’t cleaned it for twenty years, it did appear that Paladin came in with good intentions. The reality, however, was the hospital had been chronically underfunded by Tenet, and was in dire financial straits.

Paladin owner Joel Freedman had a history of fixing up struggling hospitals, and thought he could come into Hahnemann and improve efficiency in the ER and get better reimbursement rates from the government for its poor patients. However:

In an early meeting with Halter, the Hahnemann C.E.O., Freedman explained that, at his other hospitals, he had profited from federal Disproportionate Share Hospital programs, which reward hospitals that serve large numbers of publicly insured patients. “What Joel did not know is that there are caps on Disproportionate Share payments in the state of Pennsylvania,” Halter said. He explained to Freedman that Hahnemann was already at its cap.

One way hospitals make up for losses treating poor patients is through “referral networks” or specialized care departments doing expensive procedures that can attract wealthy patients with good insurance. Tenet had starved Hahnemann of this revenue stream, and Freedman struggled to bring it back. His company slashed departments that did specialty surgery, and their remaining lucrative tertiary care referrals dried up.

Making matters worse, Tenet had negotiated favorable insurance reimbursement rates with private insurers based on its huge network of hospitals, and now the companies didn’t feel the need to honor those agreements. They began to simply deny claims:

[Freedman’s] forecast was based in part on the assumption that increasing in-patient admissions through the E.R. would yield greater reimbursements from insurance companies. But insurers continued to deny many Hahnemann claims, leaving Freedman incredulous.

Some doctors at the hospital attempted to make a case to one carrier:

Hoping to convince one major private insurer that it had unjustly denied claims from Hahnemann, several doctors arranged a meeting with the company. “We found a few very good cases of patients who could have died if they didn’t get care,” Kevin D’Mello, the internist, who attended the meeting, said. “And the insurance company had rejected admission.”

Freedman showed up and blew up the deal, but it’s shocking that insurers were denying emergency hospital care to their policyholders, sticking a struggling hospital with huge bills.

All these factors, and Freedman’s erratic management style, led to the eventual bankruptcy and closure of a hospital that had been serving the city since 1848. Freedman will come out of this okay, however - he structured the purchase of the hospital so he still owns the building and the property, which has been shielded from the bankruptcy (somehow). When the city tried to negotiate with him to reopen the hospital to handle COVID-19 patients during the pandemic, it didn’t go well:

In March, 2020, city officials entered negotiations with Freedman to reopen Hahnemann to house covid patients during an anticipated surge. But Freedman asked for more than four hundred thousand dollars a month to lease the facility—a rate that he said was “very reasonable.” The talks quickly broke down.

The land under Hahnemann is prime real estate in central Philly, and could be worth more than the hospital cost to purchase. It survived over twenty years of mismanagement and neglect by two different private equity firms, but one of the oldest hospitals in the country may soon be turned into condos.

T-Mobile

T-Mobile was hacked recently, and personal details on more than 50 million people were compromised. The hacker…sat…down? with the Wall Street Journal to discuss:

John Binns, a 21-year-old American who moved to Turkey a few years ago, told The Wall Street Journal he was behind the security breach. Mr. Binns, who since 2017 has used several online aliases, communicated with the Journal in Telegram messages from an account that discussed details of the hack before they were widely known.

Sure, okay. So how did he do it?

In messages with the Journal, Mr. Binns said he managed to pierce T-Mobile’s defenses after discovering in July an unprotected router exposed on the internet. He said he had been scanning T-Mobile’s known internet addresses for weak spots using a simple tool available to the public.

[…]

He said it took about a week to burrow into the servers that contained personal data about the carrier’s tens of millions of former and current customers, adding that the hack lifted troves of data around Aug. 4.

Binns is quite the character, having previously claimed he’d been kidnapped, and filing suit (without an attorney) against the CIA and FBI about a FOIA request he’d made on botnet investigations. He also felt comfortable using his real name while speaking to a major newspaper about hacking a mobile carrier. According to reports, he or someone associated with him have been trying to sell - or have sold! - the data, which I assume is more crimes on top of the existing crimes he’s done.

I often say do not talk to reporters about your crimes, et cetera, but some hackers really want an audience. Binns does not need my advice, because he did not make a mistake leading to his exposure, he really wanted to tell everyone all about it.

Short Cons

DOJ - “Four individuals have been charged in the District of Massachusetts with conspiring to deceive banks and credit card companies into processing more than $150 million in credit and debit card payments on behalf of merchants involved in prohibited and high-risk businesses, including online gambling, debt collection, debt reduction, prescription drugs, and payday lending…”

New Yorker - “Many experts on democratic governance, however, believe that efforts to upend long-settled election practices are what truly threaten to rip the country apart.”

The Gazette - “A 52-year-old Westminster woman with back problems faces $1,592.72 in E-470 toll charges because the president of the Colorado Fraternal Order of Police, who also headed the narcotics unit of the Longmont Police Department, used a stolen license plate that comes back as registered to her.”

FactCheck.Org - “A round of fictitious stories masquerading as news articles from Fox News — invoking the names and faces of prominent hosts on the channel — and other outlets have been used in recent weeks to hawk dubious products through paid Facebook advertisements.”

Tips, thoughts, or hospital cost transparency data to scammerdarkly@gmail.com