Inigo Philbrick

In June, US authorities arrested a guy named Inigo Philbrick (real name) on the island of Vanuatu. He was on the run after ripping off various people and companies involved in the art world for the last three years. Or, as the Department of Justice put it:

…he engaged from about 2016 to 2019 in a plot “to defraud multiple individuals and entities in the art market located in the New York metropolitan area and abroad” in order to finance his art business.

I love writing about art fraud. It’s a glimpse inside the world of the ultra-rich - art is a status symbol, and the wealthy throw nearly infinite sums at it. So, how did Philbrick separate these marks from their money?

Back in April, I wrote about passion assets which are, loosely, very expensive things most people cannot afford to own outright. One way to get around this problem is to own a piece of an expensive thing. You can tell people you’re part owner of a Basquiat, even though you may only own 1/100th of the painting. Better yet, these investment companies promise financial gains when the art sells. Great!

Philbrick set himself up as a middleman in high-dollar art deals:

Instead, he operated as a reseller, becoming one of a select number of dealers whose companies sold art not just to individual collectors, but also to groups of them.

The way this works is that clients (sometimes referred to in the trade as “specullectors”) buy ownership stakes in things like Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirror Rooms” and stainless-steel Donald Judd sculptures.

While these investors often have title to the works and occasionally even buy them in their entirety, they do not typically keep them in their homes or offices. The idea is transparently about resale: art collecting as stock investing. Money is earned on the flip, with the potential for risk differing from the stock market in important ways.

Specullectors. Sure. What these deals did was create additional layers of complexity - all the parties had to trust that Philbrick was getting a good price on the deal, and that what he was selling them was real:

First, it is hard to verify the prices secondary market dealers pay to acquire and sell works on behalf of multiple investors. That enables these dealers to lie about prices, overcharge clients and skim off the top. Second, when a work is acquired and placed in storage, little assurance exists besides a dealer’s reputation that a 50 percent share in a painting is actually a 50 percent share.

You’ll never guess what happened next! Just kidding, of course you know. Philbrick created a web of buyers and sellers - using money from one deal to make more, or pay off debts. Eventually, as investors started to ask questions, he turned to forgery:

Even better, he produced for Mr. Tumpel documents from Christie’s showing that there was a guarantee on the painting of $9 million. If it fetched less than that amount, during the upcoming spring auction, Christie’s would pay the remaining balance—which the auction house and its competitors sometimes do when jockeying against one another to sell highly desirable works.

Then the hammer fell at $5.5 million.

[…]

Soon, Mr. Tumpel received an email from Jason Pollack, the general counsel of Christie’s, who had looked at the document about the guarantee and determined, as later filed in court papers, that it was likely “falsified.”

This deal was particularly fraught, because Philbrick didn’t own the painting - the money was owed to an investment company who he’d sold it to years before. The winner of the auction - who’d been one of the original purchasers of the painting with Philbrick - didn’t receive it either, because Philbrick and his accomplice hadn’t paid the auction house, sending it elsewhere. I have read the Times’s account of this sale five times now and it still barely makes sense to me. Rich people have way too much time on their hands.

Philbrick spent years brokering hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of deals. Was it a Ponzi? Probably, in a way that many frauds are Ponzi schemes - Philbrick realized, at some point, that he couldn’t deliver the investment returns he had been promising, and turned his talents to concocting elaborate financial schemes to get more money. Did I mention he was 24 when he opened his first gallery? What is it with people and trusting young, charismatic charlatans with obscenely large amounts of money?

Anyhow, as lawsuits started to rain down on Philbrick he skipped the country. I am glad he did, because it led the New York Times to publish this wonderful paragraph:

As Mr. Philbrick’s associates became convinced there was little chance of recovering their money directly from him, they looked for other ways to be made whole. So they started suing each other.

I love it! A bunch of rich idiots in a circular firing squad as Inigo was sitting on an island in the Pacific. As with all things wealthy the lawyers are the real winners here.

The article talks about a guy named Kenny Schachter who writes for ArtNet, a website I often reference when I write about art. Apparently he was a friend of Philbrick’s and one of the people he scammed. I guess if you’re an art blogger you can also afford to go in on multi-million dollar paintings? I don’t know. He had some thoughts:

Mr. Schachter still believes that his former associate had no master plan to cheat people. “In no way is it possible that he had a criminal enterprise planned from the beginning,” he said.

Instead, Mr. Schachter posited that Mr. Philbrick got overleveraged and resorted to fraud, seeking to maintain his lifestyle.

[…]

“I said, ‘You’re like ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley,’” Mr. Schachter continued. “[Philbrick] wrote back, ‘Google how the movie ended.’”

So Mr. Schachter did. It turns out Ripley strangles the person who may be about to expose him.

He made a video of himself waiting for Philbrick to be repatriated to the states and it’s…something:

The art world is so weird.

Russian Bank Bonds

This piece in Alphaville has a great lede:

An owner of a fertiliser company and wine merchant walk into a Russian bank.

That may sound like the first line of a below-average joke but in 2017 these two individuals, along with close to 250 other savers, did so and walked out proud owners of $240m of guaranteed loan notes.

As it turns out, the joke was on the investors. And it wasn’t a funny one. Three years later, they are embroiled in a legal battle that stretches across the European continent.

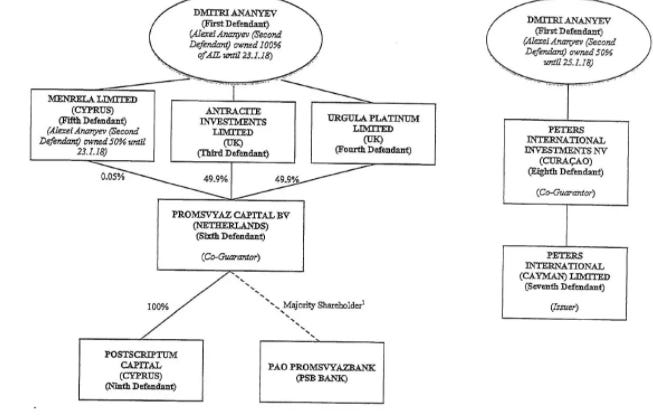

I talk quite a bit about how the financial system is mostly a money laundering apparatus for the rich. This bond deal at PSB, a large Russian bank founded by two billionaire brothers, is a case in point.

The story is, basically, PSB issued bonds to investors that carried a 5% return and were guaranteed by other companies the brothers owned. Then, later that year, the Russian government stepped in and nationalized the bank. The brothers fled the country, and authorities have charged them with embezzlement and money laundering. Sounds serious, right? Turns out it’s not all that uncommon, as the Russian government has been taking over banks for years now:

[…] by some estimates, the proportion of banking assets classed as ‘government-controlled’ has jumped from 58 per cent in 2016 to above 70 per cent now.

Unlike a PE operation, however, Putin’s people -- in this case led by Central Bank of Russia governor Elvira Nabiullina -- are not paying takeover premiums to those ‘selling out.’ In fact, in many cases they are not paying any money at all.

It’s simply a quiet nationalisation of the Russian banking system, seemingly without compensation for those who set up the hundreds of banks established in the 1990s as the country grappled with the then new-fangled concept of market capitalism.

This may seem crazy to Westerners, but it’s worth noting that Russia has an economy smaller than the state of Texas. It’s a poor country, made poorer by its leaders and oligarchs looting it for decades. For years, Putin created relative prosperity in Russia because oil prices stayed high - now that they’ve plummeted he must crack down on dissent, stoke social divisions, and keep his ruling class in line. It’s not great.

Anyhow, the bank bonds in question are a great illustration of how the rich use the financial and legal systems to avoid accountability. The 250 people who lent $240 million dollars to the bank - before the government took it over and wiped them out - can’t figure out where to sue the brothers to get their money back. They’ve tried a few things, with comical results:

The first port of call for one group of noteholders was London’s High Court, chosen because it was the domicile of two of the brothers’ companies.

It was initially successful. The High Court granted a freezing order on the brothers assets - which the noteholders said included ski chalets in Megeve, France and two Bombardier Challenger corporate jets — in July 2018. The order was lifted several weeks later when Dmitri paid the frozen amount to the court. But in September last year a judge decided England was not the correct jurisdiction and ordered the money to be repaid to Dmitri.

Some of them sued Dmitri in London and won, but then…they lost on appeal and had to give the money back? Oh man, that must have stung. Politicians in the UK and Europe are making a fuss:

Meanwhile, the scandal is becoming increasingly international. A member of Germany’s Bundestag has written to authorities in Cyprus, as well as to UK Home Secretary Priti Patel and the National Crime Agency, as he says some German and US citizens are also victims. A second member of the Bundestag has written to the European Banking Authority.

The two German MPs, who call the brothers actions a “fraud”, say the “increased internationality” of frauds “leaves national legal systems unable to cope with such cases” and are calling for more international co-operation.

Stepping back, I’d like to point out how ridiculous this entire situation is. These ultra-rich people loaned money to a Russian bank in exchange for five percent returns on their investment, which is around half what they’d get just investing in boring old stock index funds. Now they’re going to spend millions of dollars chasing their investment around the globe, as the two Russian billionaires who used to own the bank flee in their matching private jets.

Matt Levine has a “boredom markets hypothesis” which posits that sometimes markets go up - especially during the pandemic - because people have nothing better to do, so they go online and buy stocks. My market theory is that the rich and their asset managers have a need to do something with their money other than put it in a boring index fund. It’s an active management paradox - doing things with your money accrues fees, and is more likely to result in losses, but a trader or financial planner is being paid to do things with money, so they have to keep doing things or they’ll be fired and replaced by someone who claims they can do more things.

And so, we have a couple hundred rich people who shelled out at least a million dollars apiece to a Russian bank in exchange for a promise of middling returns because some asset manager told them this was a good idea? I imagine when you have a certain level of wealth all these folks come out of the woodwork to pitch you on investment ideas that can’t miss - but what is exciting about a 5% bond at a Russian bank? I don’t get it. Maybe I don’t understand finance at all.

Amazon

In recent years, Amazon has gone from being the place you bought books on the Internet to an umbrella corporation with a bunch of businesses that do different things. They’re the world’s biggest cloud hosting company, they’re a marketplace, they’re a private-label manufacturer. In April I wrote about how Amazon employees used marketplace data to create products under their own brand. Well, the WSJ is back with another article about how Amazon does the same thing with its investment arm:

In some cases, Amazon’s decision to launch a competing product devastated the business in which it invested. In other cases, it met with startups about potential takeovers, sought to understand how their technology works, then declined to invest and later introduced similar Amazon-branded products, according to some of the entrepreneurs and investors.

[…]

Former Amazon employees involved in previous deals say the company is so growth-oriented and competitive, and its innovation capabilities so vast, that it frequently can’t resist trying to develop new technologies—even when they compete with startups in which the company has invested.

Seems good! In 2015, Amazon launched its Alexa investment fund, and has made many investments. Some of them didn’t go so great:

Some investors and people involved with the deal said Amazon assured them and Nucleus’s leadership it wasn’t working on a competing product.

After striking the deal, the Alexa Fund got access to Nucleus’s financials, strategic plans and other proprietary information, these people said. Eight months later, Amazon announced its Echo Show device, an Alexa-enabled video-chat device that did many of the same things as Nucleus’s product.

[…]

Before Amazon introduced its product, the Nucleus device was sold at major retailers such as Home Depot, Lowe’s and Best Buy. Once the Echo began selling, those sales declined sharply and retailers stopped placing orders, said two people involved in the deal.

Nucleus threatened to sue Amazon, which settled with Nucleus for $5 million without admitting wrongdoing, according to people familiar with the settlement. Both sides agreed not to discuss the matter.

The classic “we are paying you millions of dollars, but we didn’t do anything wrong” settlement. When people talk about monopolies it can be confusing, but this sort of behavior is exactly what laws against corporate consolidation are meant to prevent. Companies feel pressured to go to deep-pocketed firms like Amazon for investment, but nothing is stopping Amazon from stealing their technology and integrating it into other product lines - in fact, the company’s growth-at-all-costs mindset encourages its executives to steal ideas to boost their numbers.

The tech giants no longer innovate. Maybe it’s not possible when you reach a certain size, like Google and Amazon. The incentives change, and the focus shifts to stock price, or profitability of gigantic business units. If these companies were growing huge by doing the things they were initially created to do - if Google only did search, and Amazon only sold books - that might be fine, but the pressure to make more and more money has forced the companies to expand into such behemoths they overwhelm or destroy anything in their path. This isn’t good for business, innovation, or consumers.

Fortnite

Apple has been in the news recently for restrictive policies on its App Store. Apple forces companies who want to sell services via their apps to pay - they have carved out a few exceptions, covering apps like Netflix and Spotify, but apps with premium features or virtual currency generally have to give up to 30% of each sale to Apple. App makers, unsurprisingly, are not happy about this. The company is now facing its biggest challenge, as the maker of the wildly popular video game Fortnite is refusing to pay:

Epic Games, the North Carolina-based developer behind Fortnite and other games, announced on Thursday morning that players who want to buy Fortnite’s virtual currency no longer have to buy it via Apple’s App Store. Instead, they can buy it directly from Epic. The difference for players, however, is that Epic will charge them 20 percent less if they buy the currency from Epic instead of Apple.

Gauntlet thrown! In the latest round of antitrust hearings on Capitol Hill, Apple took the least heat for anti-competitive practices, but only because its app extortion racket has flown under the radar for years. Now, with Epic Games staring them down, more people will take notice. Imagine you spend months or years building an app, it becomes popular on the App Store, and Apple tells you they are entitled to 30% of all your revenues for…reasons? Credit card payment fees are less than 3%. Apple is taking a 27% cut for hosting your little bit of computer code and letting people search for it in a store. Good work if you can get it.

Google does the same thing on the Play Store, but there are ways around it because Android phones can load apps from other sources. Apple has complete control over everything than runs on their operating system - a feature many users love, but one that gives Apple incredible leverage over the independent app makers who fuel the popularity of their devices. Sensing a pattern?

Update: before I could even finish writing this piece, Apple kicked Fortnite off the App Store

Short Cons

Business Insider - “Scammers are already profiting from selling fake views on Reels, Instagram's short-form video feature that only launched on August 5.”

Wired - “Their mug shots, photos of the two men looking tired and disgruntled in orange jumpsuits, would be plastered across the internet: “2 charged say they were hired to break into Iowa courthouse,””

Vice - “Criminals use so-called Russian, encrypted, or white SIMs to change their phone number, add voice manipulation to their calls, and try to stay ahead of law enforcement.”

Tips, thoughts, Fortnite skins to scammerdarkly@gmail.com